Learning to grieve - with love, kindness and forgiveness: Sharon's story

updated on May 29, 2020

Sharon’s world fell apart the day her son took his own life. She was stuck in a destructive cycle, and felt completely alone. But with antidepressants, mindfulness tools, and the positive inspiration of others around her, she is learning how to cope

When we lose someone, we’re reminded that it’s part of the circle of life, that we should have faith in loved ones being in a better place, an eternal life where we will all be together again, to create a picture that death is tolerable.

What we don’t expect is that when someone we love dies, grief begins and uncontrollable emotions, thoughts, and behaviours can take over the life we once knew. The thoughts of the circle of life or heaven sounds wonderful, but it doesn’t fill the void or the unbearable pain we now have in our hearts.

I want to tell you about my first experiences of death, and how on that day the old Sharon died, too. Everything I was, and everything I believed in, no longer existed. For a long time, the only thing that survived was the presence of a body, barely existing, not living – a broken spirit.

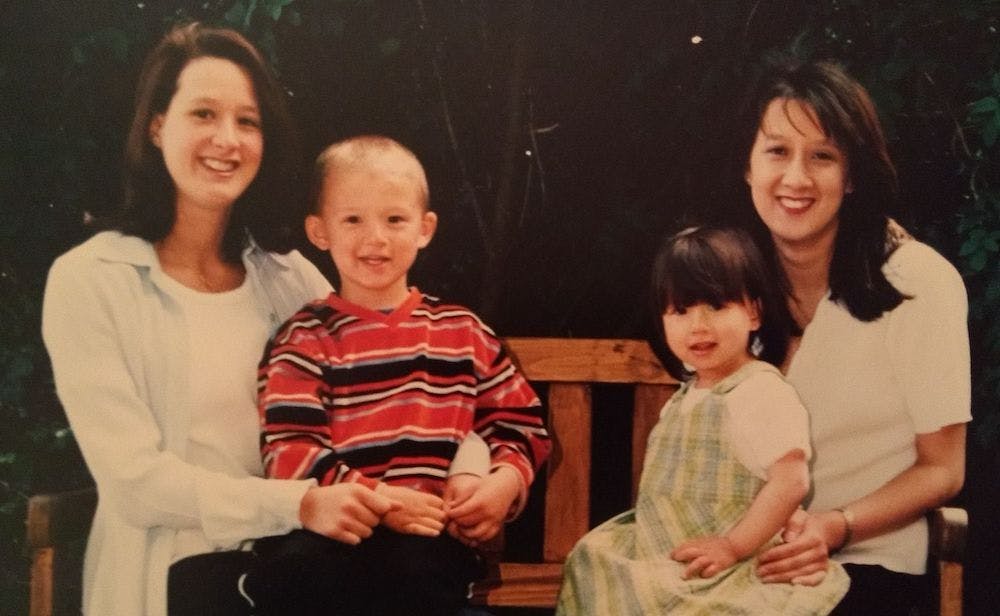

Before that day, Sharon was a meticulous, youth worker in special education for the Education Authority for Northern Ireland. I was a mother to four beautiful children – Matthew, 17, Natasha, 15, Annie Jean, eight, and Daniel, one. Living alone with the children had its challenges, but I loved my family, and always put their needs first.

Things began as usual on Thursday 11 October 2012; the alarm beeped, and it was time to wake the girls for school, and Matthew for work. Daniel was teething and, thankfully, was being looked after by his father. I went outside to a detached annex to wake up Matthew, but as I opened the door I found my oldest, first-born son was dead. He had taken his own life. My heart broke, and a part of me died with him.

Matthew had struggled with his mental health from a young age. Unfortunately, professional support was limited – Matthew would display self-harm, I’d take him to the doctors, and a referral was made to a specialist support service. With long waiting lists due to a shortage of resources, by the time contact was made Matthew’s behaviour had improved, and so no intervention took place. This was a repeated pattern.

The May before Matthew died, we visited a GP. When they asked how they could help, Matthew replied: “Give me a lethal injection.” He was referred to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). After crying while detailing Matthew’s self-harm, and his previous suicide attempt to the psychiatrist, social worker and counsellor sitting before me, I was told that as a youth worker with ‘more’ resources, I should put him on an anger management programme. No other support was given. My son died without any medical intervention.

Remembering this still brings me much heartache and pain. Matthew had been growing into such a lovely young man; making plans for his 18th birthday, learning to drive, he was the one who always told jokes, and helped me bring all the shopping bags in from the car.

The first year after he died was spent in what professionals would call the ‘grief cycle’, but to me felt like I was going mad. Wearing Matthew’s socks, sitting at his graveside for hours, unable to sleep due to flashbacks, and forgetting to eat, didn’t fit nicely into the grief cycle.

When I was reliving the past, I learned mindfulness tools to bring me back to the present

Two weeks after Matthew’s death, I was making plans to join him. I somehow managed to phone a helpline and decided I needed to live to support others like Matthew and me, who weren’t able to get help.

For a while this thought helped, until Mother’s Day when the suicidal thoughts returned. Standing in my bedroom I cried for help, but no one was there to hear me – except out the corner of my eye I saw my Bible. I had my arguments with God – why me? Why Matthew? As I cried, prayed, screamed and shouted, I ended up living another day.

I never truly told anyone how I was feeling. To cope, I started to drink alcohol to sleep, and used online shopping auctions to feel some sense of control. But while I thought no one was noticing, my daughter Natasha, and my partner Terry, started to subtly talk to me.

As life went on for others, I was stuck. I lost all motivation. As the accumulation of debt and addiction to drink was pointed out to me, I decided something had to change.

I was doing a counselling course, and while I was learning how to treat others without judgement, and with respect – which felt easy to do – the hardest learning was practising this on myself.

I went to my GP and agreed to take an antidepressant, and in turn my sleep and mood improved. I saw a counsellor for nine months, and learned to forgive myself, accepting that the only thing I have control over is me. I started to listen to my feelings, and acknowledged my behaviours and thoughts. Where my thoughts were negative, I looked for the positives. When I was reliving the past, I learned mindfulness tools to bring me back to the present. When my feelings became uncontrollable, I practised breathing skills to allow me to be more in control and focused.

I had to retrain myself to make sure I got up in the morning, made the bed, ate breakfast, lunch and dinner. The days I didn’t want to do anything, I made myself get out. Some days, even opening a letter was a chore, so I gave myself praise for all the things that I was doing. I stood in front of the mirror and gave myself positive affirmations, and slowly I started to cope better.

During this journey I was inspired by others: friends who would help with practical things, such as making me a sandwich, and allowing me to talk; the community helping people feel valued by placing painted stones with positive messages in public gardens; and donations of a bench to encourage people to sit.

I found books helpful, and was inspired by those who shared their story. In October 2019, I felt strong enough to publish my story, Forever Young. Through sharing my personal experience, I hope to support others who have been affected by suicide, and help break the stigma.

While grieving the loss of my son, I learned how important talking and taking care of myself has been to my recovery. To do this sincerely, I had to show myself love, kindness, and forgiveness. There are support services out there, but with limited resources, I learned self-help techniques I could use until they became available. I finally learned that I didn’t have to be on my own.

Graeme Orr | MBACP (Accred) UKRCP

Sharon was in a cycle of despair and uncontrolled emotions after her son took his own life. She used unhelpful coping behaviours as she struggled to accept his death, and felt stuck. Yet as she allowed herself to accept help, and began to understand her feelings, she offered herself compassion. And, in turn, things changed; she started to take better care of herself. When we’re struggling, it’s important to use our support networks, as they help us on our journey to recovery.