Christian Russo thought he had missed the opportunity to start a family. Then one day, four wonderful kids appeared in his life

A year ago, I was approaching my 40th birthday. After the demise of a five-year relationship that I was certain would lead to marriage and children, I found myself duly accepting a life without any kids of my own. I told myself that I’d be fine. I’d even begun to rationalise: I could travel on a whim, spend as I saw fit, buy more motorcycles, maybe even live overseas again. Deep down, I would’ve set all those opportunities alight for a child of my own.

As I write this, I’m sitting in a noisy games room at a caravan park on Australia’s south coast, hiding from a storm. My girlfriend’s four kids are huddled around one of those claw games, giving each other advice on how to fish chocolates out of it. My girlfriend, Ocean, who I spent nearly three years with in my early 20s, is standing behind them, offering advice and cheering them on. She turns occasionally and smiles at me. That smile has been burned in my memory for nearly 20 years. I’m deeply in love with her. I’m in love with her kids. I feel like I’m becoming part of this incredible family. I’m living a life I thought might have escaped me.

I was 23 when Ocean and I first fell in love. Jadyn, her firstborn, was only 11 months old. At the time, his father was often absent. Reactively, or perhaps instinctively, Jadyn latched on to me from the first time we met (his father is now very attentive and loving). We developed a strong bond. When Ocean and I broke up, I missed him very much. He’s now 17, good looking and taller than me, a diligent student, a natural athlete and a loving family man. He sometimes calls me “bro”.

I've always felt that raising children is the great work of a person's life, simultaneously the greatest sacrifice and greatest reward one could experience

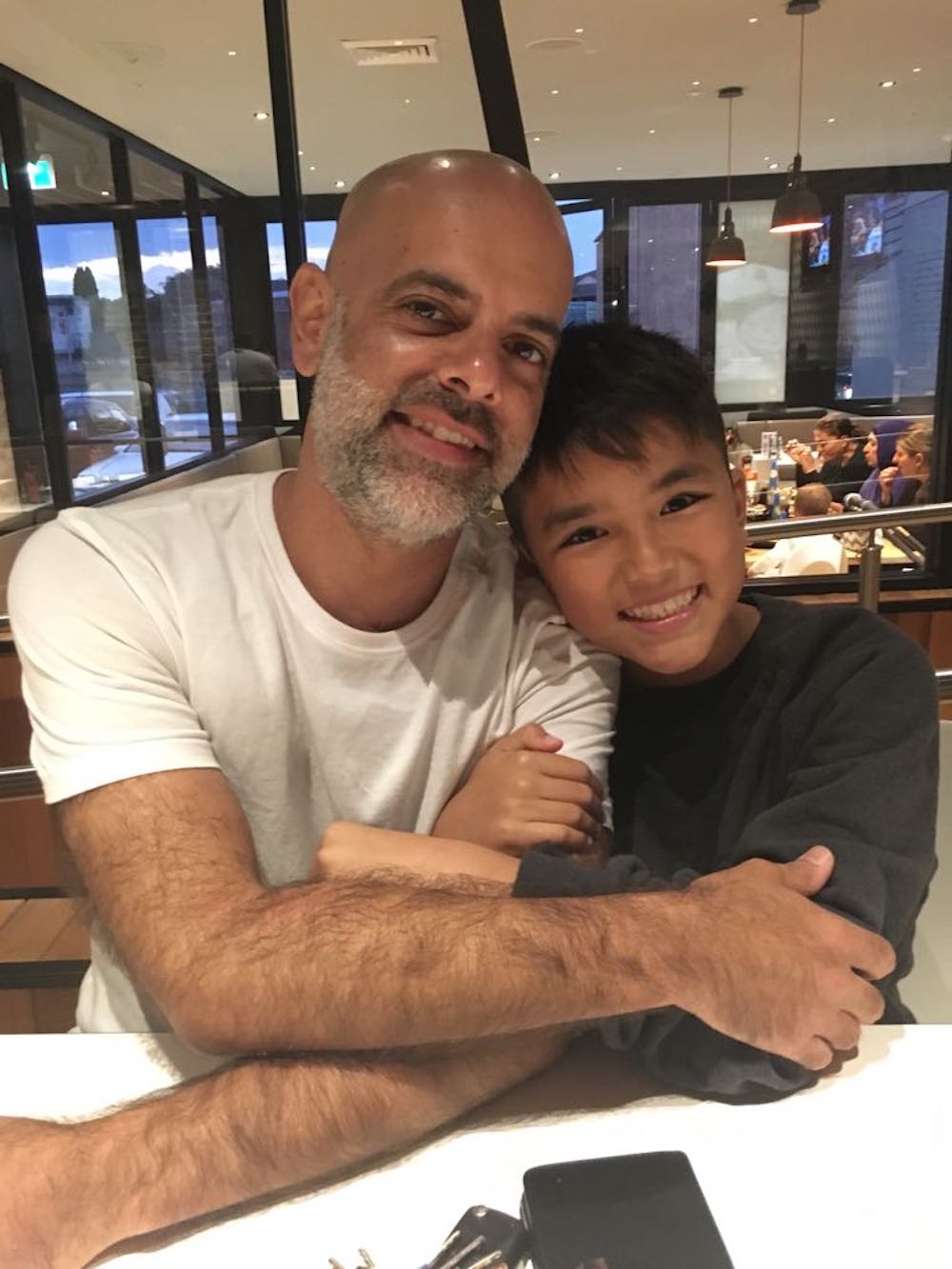

After we split, Ocean married and had three more children. George, 11, has a wild imagination, produces drawings with detail beyond most memories, loves dinosaurs, sports a huge smile and is very affectionate – which isn’t common with children diagnosed with high-functioning autism. His speech is still developing and his attention span can be short but so intense that he’s oblivious to what’s going on around him. Social interaction, his comprehension of relationships and the mechanics of family life initially proved a challenge, but he likes having me around. He comfortably slips an arm over my shoulder or his hand into mine when we walk. He recently mentioned his mother and me marrying, along with a smile. His younger sister Dora, nine, is a gorgeous young lady and too sharp for her age. She can read between the lines when adults speak. She’s effortlessly sweet when drawing you in and stingingly facetious when challenging you. She’s a straight shooter with a huge heart. And Eleni, seven, is a bundle of smiles and warmth, has a boisterous laugh, loves hugs and is hopelessly addicted to Nutella. She continually asks me to wiggle my ears for her, bursting into laughter every time I do it. Her teachers recently told Ocean that she may also be on the autism spectrum after her speech and learning raised some concerns. The prospect of further developmental issues scares me more than it does Ocean. Her love for her kids fills her with courage while I’m only just learning how to reach George.

Ocean and I have been together for just over a year now but we don’t yet live together. It’s only been about six or seven months since I first met the children. Dora proved the greatest challenge from the start. Early on in our relationship, she proudly said that “no one could replace [her] daddy,” after hearing George mention something about Ocean and I being in love. It was my first talk with one of the kids about anything to do with my relationship with their mother. I told her that I understood perfectly how she felt because no one could replace my father, either. A tear rolled down her cheek when I told her that he died a decade ago. I told her that I wasn’t even going to try to replace her dad, that I simply loved her mum and want to get to know her and her siblings better. I didn’t know what else to say so I said what came naturally. I think it worked. Earlier today, Dora and I shared a chairlift to the top of the toboggan run at the fun park we visited. We were having the kind of hyperactive chat kids get into when they’re excited. George zipped by below us on a toboggan. Dora called out to him and waved. “George is my best friend,” she explained.

I'm not their father, not quite a friend, not an uncle or relative. Yet I eat dinner with them, occasionally kiss them goodnight, and I love their mother

Dora told me he has a bigger imagination than anyone she knows. Dropping her tone a little, she said she sometimes feels like she’s a big sister to George. I sensed such sensitivity and consideration behind her words that I had to respond with gentle honesty. I told her that she’d probably find herself being the bigger sister more often as she got older. She gave me a wistful “yeah” as she kept her gaze on the passing grass below. That she thought such a thing made me love her more. That she shared it with me is a small miracle.

This is an awkward position to be in. I’m not their father, not quite a friend, not an uncle or relative. Yet, I eat dinner with them, occasionally kiss them goodnight, and I love their mother. I know that it’s not my job to be anyone’s father – those jobs are very well occupied – but they’ve tested me when we’ve been alone by doing things they know their mother wouldn’t let them get away with, and that puts me in a no-man’s-land of sorts: it’s not my place to discipline them but I don’t want to appear to condone what their mother wouldn’t allow and I’ll admit that I feel somewhat compelled to give them a nudge in the right direction. It’s tricky so I choose my moments, my tone and my words carefully. I’m not their father but, like it or not, I’m in a position where I can influence these children.

And I do like it. I love it, actually. I enjoy the responsibility. My actions have more meaning now. At the very least I’ll have some measure of influence on the standards to which these children hold the men in their lives. So I watch my step, my tone and my manner. I don’t do anger like I used to. I choose my battles and my words carefully. I don’t ever scold the children. I have other ways to reach them, when necessary. Jadyn appreciates being spoken to like the mature young man that he is; I can appeal to Dora’s intellect; I can reach George with the right tone and an arm over his shoulder. Eleni’s grin tells me she knows when she’s being naughty (it appears to have been singularly designed to melt my resolve). I hold my ground, albeit weakly and with little-to-no inclination to do anything but smile back at that lovely little thing.

I’ve always felt that raising children is the great work of a person’s life, simultaneously the greatest sacrifice and greatest reward one could experience. I’m no one’s father but, nonetheless, I feel love and pride when I’m with them. I feel like I’m doing what I was always supposed to do. I always hoped that I could pass on some of the love my father passed onto me and I see a real chance to do that with these kids. I’m part of a second family, one that might even grow one day in the future. It’s an extraordinary, enriching experience.