Since her rise to fame on I’m a Celebrity and The Jump, Amy Willerton has sought to balance her public celebrity with her private life. Now the former Miss Universe Great Britain has found a new role – as an ambassador for the National Autistic Society

happiful magazine / Joseph Sinclair Photography

We are driving somewhere through south London on the way to Amy Willerton's next appointment when the driver makes a wrong turn and stops for directions. So I’m alone in the back seat with the former Miss Universe Great Britain and I glance at her side profile. She really is strikingly beautiful. Amy doesn’t notice me because she’s eating a sandwich. It’s been a busy day. I start talking about her recent TV appearances. As an ambassador for the National Autistic Society, she’s been doing the rounds on the daytime shows, drumming up awareness. Amy says she loves live TV. Aren’t you nervous, I ask, of talking to millions in front of the camera? Apparently not. “If you have a script in your head and you’re trying to remember certain phrases, it never works,” she says. “The best way is to improvise while being yourself, because if you slip up and make mistakes you’re slipping up in your own way, and people immediately recognise the real you.”

It’s a savvy observation for a 24-year-old. I’ve interviewed Hollywood stars twice her age who admit to freezing up on live TV, but this former beauty pageant queen and star of I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here! and The Jump seems unfazed. “I like being out my comfort zone,” she says. “I guess I love the freedom.”

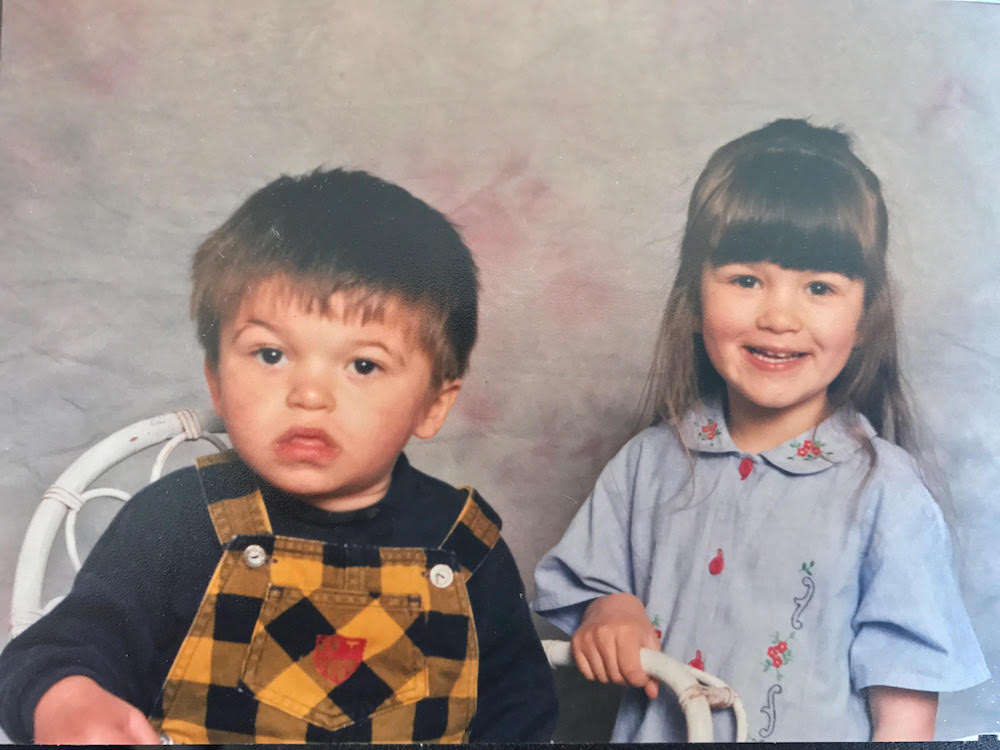

To understand why Amy Willerton loves freedom, we have to look at her background, which is pretty unremarkable except for one remarkable thing. She comes from a normal middle class family in Bristol. Her mum, Sarah, is a teacher and her dad, Bruce, now retired, is a keen gardener. She has a younger sister, Erin. It’s a tight-knit family, mainly because Amy’s brother, Ross, is severely mentally disabled.

Ross has an ultra-rare condition called mosaicism, in which his cells have a different genetic makeup. “He was born with an extra part of a chromosome which means, mentally, he will always be a one-year-old,” she says. “It’s completely unique. There’s one other person in Australia who has something similar to him, but we don’t really have anyone we can compare him to. Scientists still don’t fully understand it.”

When Ross was nine months old, the family realised something was wrong. On top of the mosaicism, he developed severe autism, and then later, epilepsy. But Amy didn’t see it is big deal. There were only two years between them so the earliest she remembers Ross is as early as she remembers anything. She just knew he was special. “Ross doesn’t know he’s got anything wrong with him. He’s got no idea. For me that’s one of the best things. Conditions where children are mentally fine but can’t physically move are a lot more torturous, whereas my brother is in la-la land and just wants to talk about Winnie-the-Pooh.”

The simplest way to describe Ross is to see him as a toddler in a 6ft 4in man’s body. He has full physical capabilities but no speech. Amy communicates with him using Makaton sign language. When he can’t communicate, Ross has what Amy calls ‘frustration fits’. Unlike us, he’s got no way of telling someone if something is wrong. “He used to throw his head against the wall. It was awful,” she says. “But with Makaton it allows him to tell us when something is not right.” Her family learned through trial and error. “His brain works very differently to how our minds work, so we had to re-wire everything backwards and make decisions that on the surface make no sense.”

I don't want to spend more time taking pictures of something than I do actually experiencing it. I'd rather live in the moment

As Ross grew older, Amy remembers the tremendous arguments between her parents. Her mum couldn’t accept Ross being the way he was and her dad couldn’t accept that her mum couldn’t accept. It became a barrage of intensity. Amy couldn’t bring friends over to the house because her mum was worried Ross would react badly, and she was always very insecure of people judging him. It's these experiences that propelled Amy towards the National Autistic Society, especially their campaign to improve public understanding.

When Ross was eight, the family found a special needs school, St Christopher’s, in Bristol, which Amy calls ‘the most amazing school in the world’. Ross went to live there during the week and came home at weekends. “That school changed our lives,” she says. After turning 18, Ross was moved to a Milestones Trust residential care home, where he also boards throughout the week and comes back to the family at weekends. It gives him structure. But the ideal scenario is for Amy to build a little house in her garden with a full-time carer so she can be with him all the time. “I want to work very, very hard to achieve that dream. Although he’s happy where he is, it would be nice to see him all the time and not just at the weekends.”

I ask Amy if she shares a private language with Ross, which produces squeals of laughter. “Oh god, yes I do! I make a lot of very strange noises only he understands!” Can she give me an example? “Honestly," she giggles, "I can’t make the noises I make for Ross with you!”

She says Ross, now 22, is an amazing judge of character. “I’ve been more worried about bringing my boyfriends home to meet my brother than I am my dad. If my brother doesn’t like you he’s not going to hide it. My dad’s quite polite, but Ross has no problem leading you out the door and then shutting it in your face. No qualms!”

As for her parents, Amy says they are now closer than ever because they have fought the battles together. “I can’t see them ever splitting up,” she says.

When she talks about family, or relationships, I sense a brooding shadow lingering over some of her words, and it soon comes to light. “I also have a cousin with severe autism, and another cousin with Down’s syndrome, and all on my dad’s side of the family,” she says. “It’s really worrying because I want to have children some day and when I look at my family pattern there are three children with disabilities all in one generation. It’s scary.”

Has she taken the tests? “Yes, they told me it’s not genetic, it’s just bad luck. They said it can’t get passed on, but in my head it’s too ironic.” And she definitely wants children? “Definitely. When the time comes for me to have kids I will re-take the test and find out what’s causing this to happen in my family. There’s now non-invasive testing for unborn babies, and although that brings up a whole conflict of ethics, for me it’s something that’s a really good progression because, having lived and dealt with our situation, I think it’s important to decide if it’s something you want to take on, because it’s a lifelong job. They never grow up and they never leave home. They will always be children.”

I measure success by how happy I am. Why put pressure on yourself if it's going to make you miserable?

Amy calls Ross her inspiration. “He makes all my problems seem very small. When I’m scared, I stop and think about Ross. At least I have the ability to do things, right? Imagine if I didn’t have the physical ability to go on The Jump? He pushes me to be a better person.”

She radiates natural confidence, so it’s a surprise to discover she was bullied at school. Her school days were a lonely time where she struggled to make friends. She was a quiet and shy child who sat in the background. “I was never in a gang. I never had a girl squad. I was always a loner. A lot of bullying is about segregation where you're made to feel like you’re not good enough. I kept trying to prove to people I was good enough. Eventually you have to go your own way. That’s when I stopped making decisions based around people who didn’t care about me and started to become the person I wanted to be.”

There was a defining moment at school when she saw a girl with learning disabilities being bullied by a girl squad. They were taking pictures of the girl and then posting them online with horrendous comments. Even though Amy herself was being bullied, she stormed into the cafeteria and took the girls to task in front of the entire school. It was a proper shouting fest. “I completely lost the plot,” she says. “But I actually got a lot of respect for it. I was shaking afterwards, but it was something that had to be said because nobody was defending this girl and she didn’t know it was happening. I always found it very difficult to keep my mouth shut.”

happiful magazine / Joseph Sinclair Photography

Soon after, her life changed dramatically.

Out of the blue, she was scouted by a modelling agent while walking down the street with her sister. “There’s a woman following us!” she whispered to Erin. The woman introduced herself and asked if she had considered modelling, which Amy thought was a joke. She had always regarded herself as uncool, with really bad acne, and she wore glasses and a brace. Her first reaction was, “Really, you want me?” She was 15.

Amy started modelling part-time for a bit of extra cash along with her babysitting income. Modelling gave her a sense of acceptance. She was also a bit of a swot. Having aced her exams, she was accepted at the University of Cardiff. That’s when she saw an advert for a Miss Bristol competition in her local newspaper. “I said to my mum, ‘I’m going to become Miss Bristol’. She thought I was mad.” They made a pact that if she won Miss Bristol, she could defer university for a year. Reluctantly, mum agreed. Amy won. “I never did end up going to university,” she says cheekily. “That one year deferment turned into six years.”

There was always plenty of modelling work, but Amy says it’s a tough business. “I saw a lot of bad things very early on in my career, so I never developed any bad relationships with food, or my self-esteem.” In one of her first modelling jobs she saw girls eating cotton wool buds to fill their stomachs without taking in calories. “I remember thinking, I never want that kind of relationship with food.”

Amy took the leap to join a major modelling agency in London, but the first thing they asked her to do was lose two stone. “I thought, nope, not interested, that’s never going to happen.” Instead, she got into her pageants in a major way. And she was winning them, all of them, including Miss Universe Great Britain, even with her extra two stone.

Her fame went through the stratosphere when she appeared on I’m a Celebrity in 2013, with 14 million people watching the show nightly. After filming, she flew home to the UK and suddenly realised everybody knew who she was. “I had just come from Miss Universe," she says, "so I had lost a lot of weight in the jungle. People saw me as this very slim girl.” Going back to normal life meant going back to eating normally, which meant putting on weight. Critics said she had gotten fat. “It actually took me a long time to accept my normal weight," she says. "The expectations were that I was this super-slim model, whereas I’ve always been a curvier girl.”

Fame scared the crap out of me. I felt I had let myself down, let my friends down, and let my parents down. I punished myself

The media scrutiny was fiendish. Amy had to apply a whole new set of rules just to survive. “With pageantry, I was always in a crown and sash. If I wanted attention I would wear my crown and sash. When I didn’t, I took them off and I was just Amy. That was my relationship with fame. I thought there was an on-and-off switch. Suddenly, I didn’t have that switch. It scared the crap out of me. I felt I had let myself down, let my friends down, my parents down. I punished myself. Fame can make you feel like you’re not yourself anymore.”

Amy hit a wall of anxiety. She was constantly worrying about going out in public and what people thought of her. “It took a lot of time before I realised you’ve got to have self- acceptance. You can’t be angry and blame yourself. You have to be more forgiving. When I make a mistake, I now ask myself what I’ve learned from that mistake. Self-acceptance allows you to make choices about who you want to be.”

Suddenly, Amy looks troubled. I ask if she’s okay. She’s worried she’s coming across as a virtue-signalling celebrity. I tell her she’s coming across as the real deal. She then tells me she used to take everything she read about herself so personally. Now her motto is ‘Don’t believe your own bullshit.’

As long as she knows who she is, and as long as her family, her friends and her boyfriend know who she is, then Amy doesn’t give a damn what anyone else thinks. "I don’t take the coverage so seriously any more. I never read the comments. I read the articles, but if it’s not how I want it to come across I don’t let it eat me up inside. And I don’t blame anyone else for my problems.”

Amy has another motto: ‘Measuring success in happiness.’ Previously, she measured success by how much money she earned, and by what people thought of her. It later dawned on her that some of her most successful times, fame-wise, were also her most miserable. “I now measure success by how happy I am," she says. "Why put pressure on yourself if it’s going to make you miserable?”

happiful magazine / Joseph Sinclair Photography

You would think the pressure of being invited to join the celebrity-crunching TV show, The Jump, would see her running for the hills. Not a chance. “I was so excited! It was more dramatic than I ever thought it would be because you’re living on the edge. You wake up every morning and fight the fear. It scares you!” She’s got to be joking. “No, I love that feeling when you’re able to break through your fears.”

Amy was involved in a horror crash during filming and the bookies expected her to quit. She spent nearly a week in recovery doing positive meditation. “It’s not physical, it’s all mental on The Jump. Whenever I felt the panic coming on, I took myself back to a calm space and breathed out the tension.” She came back stronger and more confident than ever. This is the same Amy who used to be scared to go into shops because she was too shy to face the shopkeeper. The girl’s got guts.

She won’t name names but Amy says she has loads of friends with massive anxiety problems. “Seriously, every other person I meet has some form of anxiety. It’s so common. It’s really sad that people feel so scared.” Amy partly blames social media. “I sound like an old woman but I think we should set a limit where we live more in the real world and less in the online world. I don’t want to spend more time taking pictures of something than I do actually experiencing it. I’d rather live in the moment.”

We’re back to freedom again. “Growing up in a strict routine with Ross meant I didn’t have any freedom. Now I don’t know what’s going to happen and I find that exciting. I’m a bit of a deviant, to be honest. I like bending the rules!”

I ask Amy about future projects and it’s all she can do to stop herself from breaking the rules and blurting out her media calendar. She wants to do more live TV, more TV challenges, and she’s got her own haircare range coming out, so we can add entrepreneur to her credits. Her mission is to build a brand that runs on its own. Why? Because it will give Ross his dream home, and allow her absolute freedom. Somewhat awkwardly, I ask Amy to define the essence of freedom. Quick as a shot she fires back the famous quip from John Lennon. “Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans – that’s me.”

happiful magazine / Joseph Sinclair Photography

Photography | Joseph Sinclair

Styling | Kate Barbour

Hair | Alice Theobald at Joy Goodman using Lanza

Make-up | Roisin Donaghy at Joy Goodman using Mac and Ark Skincare